Dan Simmons' Hyperion

One of the most beautifully rendered science fiction universes ever, is created by master story teller Dan Simmons.

In Hyperion, Dan Simmons accomplished the creation of one of the most beautifully rendered science fiction universes ever encountered in the readers mind. Hyperion tells the story of a group of seven strangers on their way to the distant world of Hyperion. Earth is dead, but humanity has spread among the stars in a web of worlds (connected by an FTL transportation system called The Web) known as the Hegemony. There are worlds humans live on which are not a part of the Hegemony, but that number is in constant decline as the benefits of conformity outweigh the benefits of independence. Somewhere in the galaxy, a self-aware collective of artificial intelligence known as the TechnoCore have made their home, helping the Hegemony to care for its technology. Also spread in between the stars are the Ousters, “barbarians,” who roam in Zero-G mobile cities and flotilla, attacking Hegemony targets whenever the opportunity presents itself.

The world of Hyperion itself is mysterious and terrifying. A deadly forest full of “Tesla trees” hides a lost human tribe who can only refer to themselves as the “Three Score and Ten.” Below the surface of the planet is an extensive labyrinth. The likeness of the Legendary Sad King Billy looms over the capital city of Keats in a rough statue. Most terrible of all, however, are the Time Tombs. Strange stone structures that move backwards through time and house the Shrike, a monster that seems to kill for killing’s sake.

A threatened Ouster attack on Hyperion has led the Shrike Church, a faith that worships the monster as an agent of God’s wrath, to attempt one final pilgrimage. The seven strangers, each with a connection to Hyperion, travel together to the Time Tombs, and each tells his or her story at some point on the trip. The reader also learns that while nearly all of them will be killed by the Shrike, one pilgrim will be able to make a wish to the creature. The pilgrimage thus operates as a frame story, an excuse to hear from the diverse perspectives of a poet, a politician, a professor, a soldier, and so on. The interpersonal interactions between the characters are informed by their contrasting personalities and varying motives.

Hyperion’s Canterbury-Tales

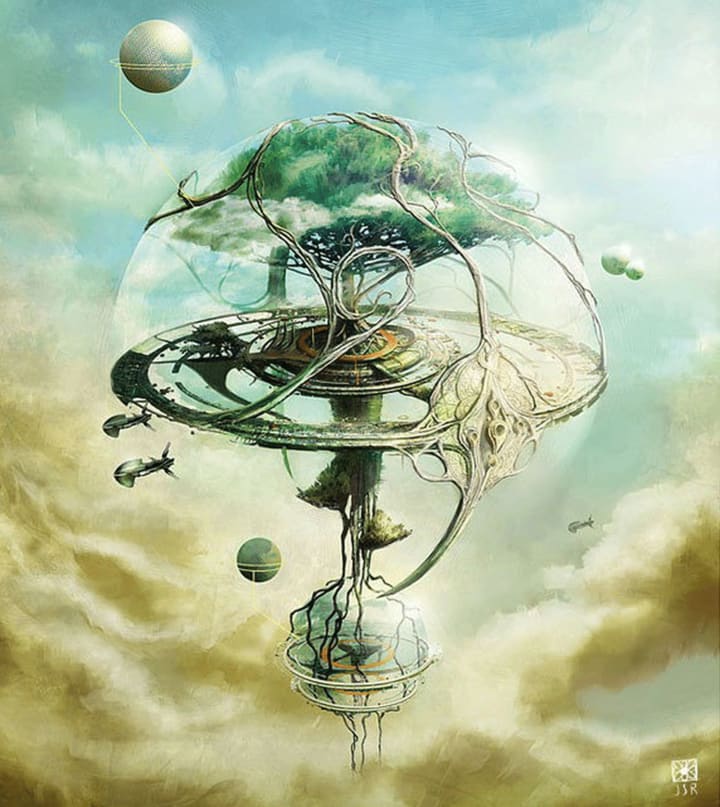

Yggdrasil tree ship by J. S. Rossbach

Hyperion’s Canterbury Tales style is a somewhat bold move, but is a calculated risk. While the individual stories of each character would threaten the flow of the main narrative, Simmons exercises enough control to keep the story moving along. The payoff is immense. Allowing each pilgrim to tell their own story offers maximum engagement with the detailed universe which Simmons has envisioned. It also allows an impressive spread of genres, which Simmons handles deftly. The stories range from horror, to the kind of military-adventure yarn more typical of space opera, to cyberpunk romance.

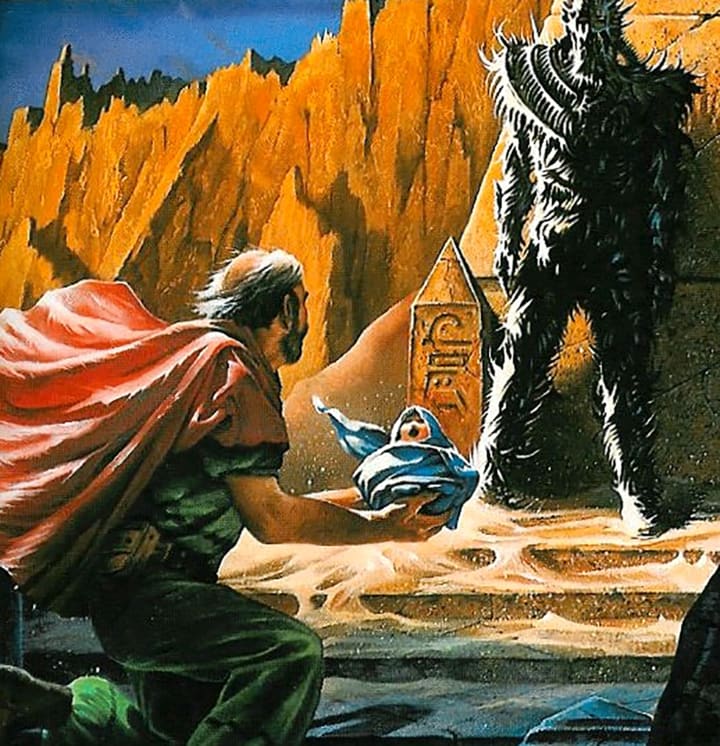

My two favorites were also the two saddest: a loose adaptation of Genesis 22 (the infamous Binding of Isaac pericope) sees a man’s daughter age backward in time and concerns his heartbreak as a dream-vision of the Shrike claims her as a sacrifice. The concluding pilgrim story makes tragic use of time dilation, as a man returns, months apart in his mind, to his lover, who ages decades in his absence. The frame story is itself rather compelling, and each chapter heightens the tension as the war between Hegemony forces and the Ousters looms closer. By the end of the book, there are battles visible in the sky.

Simmons has a masterful control of the sublime, a literary term introduced by Burke to discuss the infinitely beautiful and terrible. The sublime, when used inelegantly, can transform an otherwise enjoyable science fiction narrative into a series of day-glo distractions. Bright, but not especially beautiful or terrible. Just the right dash of it can lend an air of epic narrative to an otherwise emotional or quiet story. Think about Danny Boyle’s film Sunshine, which breaks up the cramped isolation of the Icarus with senses-shattering demonstrations of the sun’s power. As the pilgrims watch ships duel overhead with lasers and nuclear missiles, the reader becomes suddenly aware of the fact that a slight miscalculation could vaporize our heroes without anyone in the battle noticing. The purpose of the sublime is to remind humans of our smallness, and Simmons finds new and interesting ways to do so throughout his novel without losing the story in the process.

Maui-Covenant by Goran Josic

The tropical world of Maui-Covenant, for example, has its breath-taking living islands. The Tree Templars, who provide passage for the group to Hyperion, have immense Treeships. Most terrible of all is the Shrike, which operates as something of an uncertain antagonist. There is a lot of speculation by characters about the Shrike’s true nature, but in a sense the nature of the Shrike is irrelevant, so long as it is scary enough to draw the pilgrims in. The creature has glowing red eyes, four arms, is covered in sharp appendages, and can appear or disappear at will.

This proves to be its most terrifying feature, since it appears to strike at random and either cause people to disappear completely or reduce them to a red smear. There is no real clarity by the end of the novel of the Shrike’s true nature or origin, but the information we receive is enough to fire the imagination of the reader. The nature of the beast changes from pilgrim to pilgrim as well. In more than one it operates as a kind of savior, in others it fulfills its role as bogeyman.

Adding to Simmons’ hostile universe are the Ousters. The author is wise enough to note the ways in which human beings might change physically in non-earth environments. The Ousters live their lives in Zero-G, and have become nearly alien as a result. They have long prosthetic tails, black space armor with long fingers to match their thin and stretched frames, and a new language to boot. The Ousters provide the long-game external excuse to visit the world of Hyperion, but one pilgrim’s close encounter with them will have your hands sweating as they turn the page.

That pilgrim, Colonel Kassad, provides one of the most intriguing developments in the history of Simmons’ world. Simmons has taken the time to explore what the death of earth would mean to the people who populate his universe. Colonel Kassad is a Palestinian, and Simmons is a writer well-tuned to the great ironies of history. In his history, Palestine achieves independence just in time for the Earth to die. Kassad represents then not only a generous treatment of a Palestinian, but also a man at the whim of history.

Jewish Colony-World of Hebron

Sol Weintraub, another of the pilgrims, is a Jewish academic who shows the reader the Jewish colony-world of Hebron. His story plays off of biblical themes, but more intriguing is the theological question of what Judaism must look like, not only when the people are out of the land, but when the land itself, to quote the prophet Jeremiah, is “Waste and Void.” In these two examples especially, Simmons demonstrates an impeccable capacity to imagine that humanity’s future will be determined by the human response to that future. Here Asimov’s psychohistory from Foundation is lost in a bubbling cauldron of variables defined as ideology, experience, and interpretation.

One final element of this novel which I am sadly ill-equipped to comment on fully, is the recurring theme of the poet Keats. John Keats manifests himself in Hyperion’s name and capital (Keats wrote a poem titled “Hyperion”), but there is also a poet obsessed with him, an AI intended to “be” him, and a score of other references to him throughout. Simmons’ willingness to play with the Keats motif signifies that to Simmons art matters. The way in which art shapes the consciousness of humanity is manifested in the tale of his resident drunk poet, Silenus, whose poems about the dying Earth are a bestseller in the future. Hyperion is more than an example of worthy space opera. It’s a masterful meditation on art, history, terror, and truth.

About the Creator

Joshua Samuel Zook

Grew up in a religious household. Listened to countless sermons on the wrath of God. An epiphany struck him and he realized no one is that angry, not even God.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.