Economics Vs Environmental Crisis

Mankind must ask itself how far is too far before economics cause an irreversible environmental crisis.

From our wildlife being taken over to our greenhouse gases being at an all-time high, environmental crisis is forcing us to ask what, how, and why. Throughout history, there have been recurring battles between man and nature in every century, from nature versus big corporations to growth versus quality of life. In each battle, each opposing side struggles to regain control of the situation at hand. But what they really should be addressing is: When have we gone too far?

Without the environmentalists who have stood side by side with our very own Mother Nature, we might not have the liberty of seeing some of the fascinating beauty that this earth has to offer today. Environmentalists have been fighting mining and its environmental damage for decades. In the 80s, environmentalists in Utah were confronted with the ethical question of destroying natural beauty for corporate endeavors. If nature abhors a vacuum, does the industry as well?

"The Kaiparowits Plateau of southern Utah is so vast that you could drop Manhattan Island in the middle of it and never notice," said Calvin Rampton, an industry scout. "Besides, nobody ever goes there anyway."

Allen-Warner Valley Energy System

via Summit Post

Rampton, a former governor of Utah, was a consultant to seven companies that held coal leases on the Kaiparowits Plateau, which contained the richest undeveloped coal deposits in the United States. He and his employers aimed to improve the vacuum of the plateau by dropping a coal mine and a railroad into the middle of it. The railroad, necessary for bringing coal out of southern Utah's presented tracklessness, was one of the largest rail projects of its time—more than 300 miles of new track and three years of labor—costing $350 million. The mine and railway, called the Allen-Warner Valley Energy System, was one of the biggest energy projects ever undertaken in the Southwest.

One hundred years before the project was suggested, no one would have minded. The Calvin Rampton View of the Desert went unchallenged, then. Our appreciation of the aesthetic virtues of the Southwest had developed slowly. Before the southwestern terrain could look like anything but wasteland to us, we had to teach ourselves to see again.

"The lover of nature, whose perceptions have been trained in the Alps, in Italy, Germany, or New England, in the Appalachians or Cordilleras, in Scotland or Colorado, would enter this strange region with a shock, and dwell there for a time with a sense of oppression," wrote Clarence Dutton, one of southern Utah's first white visitors. "Whatsoever things he had learned to regard as beautiful and noble, he would seldom or never see. The colors would be the very ones he had learned to shun as tawdry and bizarre. But time would bring a gradual change. Some day he would suddenly become conscious that outlines which at first seemed harsh and trivial have grace and meaning, that forms which seemed grotesque are full of dignity, that magnitude which had added enormity to coarseness have become replete with strength and even majesty."

"It is lovely and terrible wilderness," wrote Wallace Stegner, "...harshly and beautifully colored, broken and worn until its bones are exposed, its great sky without a smudge or taint from Technocracy, and in hidden corners and pockets under the cliffs the sudden poetry of springs. Save a piece of a country like that intact, and it does not better in the slightest that only a few people every year will go into it. That is precisely its value."

It was the air that Willa Cather remembered. Of her fictional Father Latour returning to this desert as an old archbishop, she wrote, "He always awoke a young man, not until he rose and began to shave did he realize that he was growing older. His first consciousness was a sense of the light dry wind blowing in through the windows, with the fragrance of hot sun and sage-brush and sweet clover, a wind that made one's body feel light and one's heart cry 'to-day, to-day,' like a child's."

"Beautiful surroundings, the society of learned men, the charm of noble women, the graces of art, could not make up to him for the loss of those light-hearted mornings of the desert, for that wind that made one a boy again. He had noticed that this peculiar quality in the air of new countries vanished after they were tamed by man and made to bear harvests."

It had taken the Duttons and Stegners and Cathers, the Georgia O'Keeffes, Eliot Porters, and John Hustons, to teach us to see this country, but at last we do see it. Even our government has gotten the message, and much of this country's land is protected by law. Within a 250-mile radius of the Kaiparowits Plateau are 26 national monuments, 13 national forests, eight national parks, five Bureau of Land Management natural areas, three primitive areas, three national recreation areas, two national historical sites, and one national memorial. Twelve Indian reservations lie within the circle, and these, in turn, contain their own tribal parks and sacred landmarks.

The Allen-Warner Valley System, as Ronald Rudolph, of Friends of the Earth, has said, "drives a spike through the heartlands of our national parks."

Southwestern Coal Industry

via Wikipedia

Over the decades, southwestern coal became increasingly attractive to energy utilities. They had been drawn into the industrial vacuum of the Four Corners country by the pollution standards there, which were less strict than those of more densely inhabited areas by the boosterism of local politicians, who imagined that their constituents were bored with life in an industrial vacuum, and by the cheapness of the coal. The worst of the coal projects, from the environmentalist's point of view, was the Four Corners Power Plant, in northwestern New Mexico. That plant burned coal strip-mined from land near Shiprock, a Navajo sacred mountain, and sent skyward a smoke plume so gigantic that it was one of the few artificial phenomena visible to the astronauts of Project Gemini. Nearly as bad is the strip mine at Black Mesa, another sacred Navajo mountain. Coal from Black Mesa was burned at the Navajo Power Plant, near Page, Arizona. When the wind blew in the wrong direction, the smoke from that plant reduced visibility in the Grand Canyon to less than 15 miles.

Stegner's description, then, "great sky without a smudge or taint from Technocracy," no longer holds true in all of the Southwest. The air that Cather wrote about—light, dry, aromatic, free—has disappeared from parts of this desert.

The Allen-Warner Valley Project would eliminate what clean air was left. It had annually generated 30,810 tons of particulates, 17,024 tons of nitrogen oxides, and 3,267 tons of sulfur dioxide. Erosion from construction had damaged water quality in a region where water had always been scarce. Coal dust, heavy metals, and salts would find their way to the Colorado River. Deer antelope, elk, bighorn sheep, bald eagles, peregrine falcons, cougars, bobcats, and Utah prairie dogs would be displaced.

Mormon Dilemma

via st George News

The human population had boomed. Utah's Kane and Garfield counties, where most of the project's impact would be felt, contained just around 7,000 people at the time. The project would bring in 80,000 more. Many of the residents believed they would welcome that.

Most were Mormons. The project, many thought, would mitigate an old Mormon dilemma. Mormons are strong believers in family, yet their great 19th century migration took them to a sparse region where holding a 20th century family together was difficult. There were few opportunities for young people who, in turn, were forced to move away. Jobs that were provided by the mine and railroad would call young Mormons back from distant cities. The tax base had broadened. The church, vigorously proselytistic, would gain, in the influx of new workers, plenty of raw material for its missionary zeal.

The question, of course, was whether that influx of gentiles—tough American gypsies of the trailer-camp culture, an influx outnumbering the local population eight to one—would lie down quietly and be proselytized. Would miners and railroad men be satisfied with Utah's 3.2 beer? Would Mormon family life be improved by the alcoholism, delinquency, divorce, violence, and culture shock that inevitably follow industry into rural places?

Kane and Garfield counties shared the illusions that Fairbanks, Alaska, held before the Alaska pipeline was completed and that Gillette, Wyoming, held before the strip mine was opened there. Such illusions were only possible in places far from the city.

Industries vs Nature’s Saviors

via Wikipedia

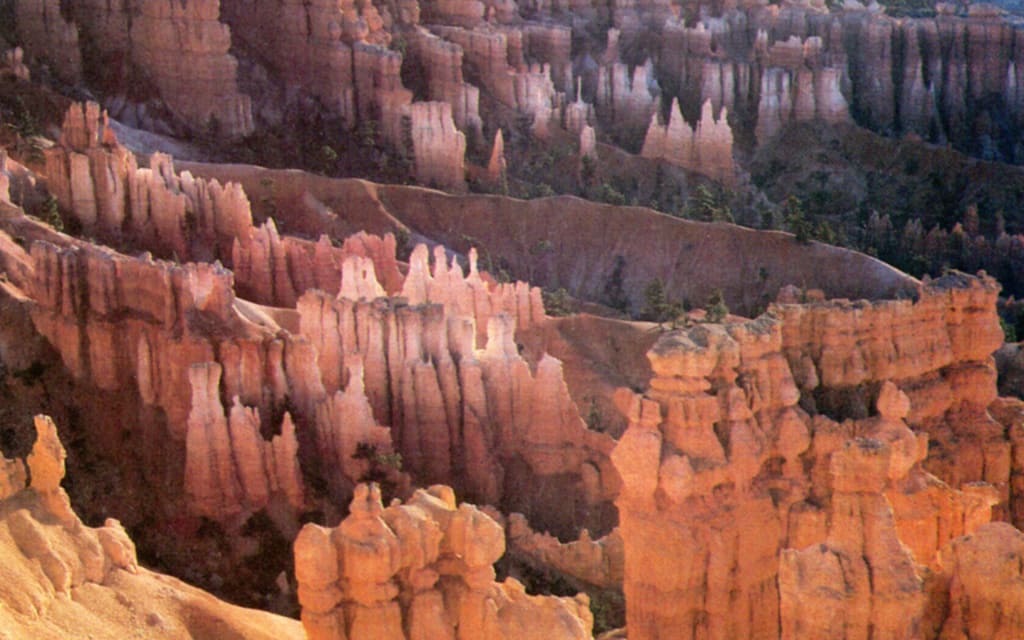

Environmentalists were preparing for the fight. Lawyers from the Environmental Defense Fund had joined forces with the Sierra Club, Friends of the Earth, and several local ranchers whose land the railroad crossed. The lawyers liked their chances. The National Park Service and the Bureau of Land Management were ranged against the project—in the personal sentiments of their personnel, at least. The mine component of the Allen-Warner System was situated just three miles from the boundary of Bryce Canyon National Park. Mining operations were visible from Yovimpa Point, one of the canyon's main scenic overlooks. Air quality in the park was impaired, and Bryce's desert silence had departed. Blasting might well tumble the delicate, Salmon-colored erosional towers for which Bryce was protected. Industries would not be able to do this to a national park, just as the environmentalist thought. They argued that the mine site could not be reclaimed in conformity with requirements of the Surface Mining and Control Act; that safer cleaner and cheaper alternatives to Kaiparowits coal existed, and that the enormous investment required by the Kaiparowits project would have precluded investment in more sensible alternatives.

"Those who haven't the strength or youth to go into it and live with it," Stegner writes of this country "can still drive up onto the shoulder of the Aquarius Plateau and simply sit and look. They can look 200 miles, clear into Colorado; and looking down over the cliffs and canyons of the San Rafael Swell and the Robbers' Roost, they can also look as deeply into themselves as anywhere I know. And if they can't even get to the places on the Aquarius where the present roads will carry them, they can simply contemplate the idea, take pleasure in the fact that such a timeless and uncontrolled part of the earth was still there."

Perhaps, with a little more luck, places such as those Stegner describes can continue to be preserved throughout the country.

Kenneth M. Sayre's Unearthed: The Economic Roots of Our Environmental Crisis, presents the arguement that the only way to resolve our current environmental crisis is to reduce our energy consumption. Sayre argues that consumption must fall below a level where the entropy (degraded energy and organization) produced by that consumption no longer exceeds the biosphere’s ability to dispose of it.

About the Creator

Kenneth Brower

American nonfiction writer; Best known for his books about the environment, national parks, and natural places.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.