Into The Expanse and Beyond: A Conversation with Television Showrunner Naren Shankar

Naren has been able to help push real science in television shows.

Naren Shankar has a long-running career in science fiction television. He's written for such critically acclaimed series as Star Trek: The Next Generation, SeaQuest DSV, Farscape, and The Outer Limits. Naren has also been a showrunner for CSI and currently serves as a showrunner for SyFy's The Expanse. Coming from a science-educated background, Naren has been able to help push real science in television shows. I had the opportunity to chat with him and get his perspective on the evolution of genre TV, his career, and all things The Expanse.

You have an amazing TV background. You’ve done so many different shows. Walk me through your origin story.

Naren Shankar: Growing up I always loved science fiction. It was one of those things that for as far back as I can remember I enjoyed. I watched Star Trek as a kid, anything—Lost in Space, which I didn’t live very much, by the way. I loved Star Trek and it was just one of those things that I devoured. I don’t know how old you are, but there was this thing when I was a kid called the Science Fiction Book Club, which was this mail away program where they would advertise “four great classics of science fiction for ten cents!” And every month you would receive a great book and that’s where I started to read amazing novels like Dune and the Foundation Trilogy.

So it was always kind of part of what I liked to do. And one of the reasons I started gravitating towards science was because of the stuff on those shows and in those books that I thought was cool and science-y. I wanted to make that stuff myself. That mindset went all the way through high school and when I got to college, I was kind of a generalist at heart.

I studied at Cornell at the College of Arts and Sciences as a Liberal Arts student. I wasn’t really sure what I wanted to do. I thought maybe pre-med, which wasn’t really what I wanted to do —maybe Medieval studies, or French literature? I did that for a couple of years and realized—maybe I won’t be able to get a job with that. So, I transferred to the College of Engineering. Usually, people transfer OUT of the College of Engineering. During that time, I joined this Greek letter social fraternity, which was also a literature society called the Kappa Alpha Society at Cornell. And part of what we did was every two weeks, we would meet and we would write and deliver new pieces to the membership. So it was this regular creative endeavor. And in the process of doing that, I had made a couple very good friends. After graduating, I decided to stay on in graduate school. I was in Applied Physics and Electrical Engineering; I had stayed on in Cornell. And one of my friends decided he was going to move out to Los Angeles and become a screenwriter. We always loved movies, we always loved television shows and that was always sort of part of late night TV watching in the fraternity. And my other friend was Ron Moore.

Ron Moore - Showrunner of Battlestar Galactica & Outlander

Ron was a political science major. About a year after our first friend went out to LA to try and become a screenwriter, he dragged Ron out there. Now, I had started college really early. I just turned 16 when I entered college. I was really young and was two years ahead of Ron, but we were the same age. I was several years into graduate school as I was working on my doctoral research. The way I describe it, I started feeling more and more like an expert on a smaller and smaller corner of the universe. And it felt kind of isolating. So what started happening is that I began taking courses in the arts, and history and literature again. Actually doing them, while I was doing my research. And what was happening was that I found that side of things extraordinarily fulfilling, and my lab rather lonely.

I actually remember the moment. I was walking back from this amazing lecture in a course that I was taking on the history of American foreign policy. This yearlong course by a brilliant lecturer named Walter LaFeber. And I walked out of this lecture and I was heading to my lab and I was thinking, “Fuck, I can’t be an engineer.” (Laughter)

It was literally that kind of moment. But I had about a year and a half to go —and so, I gutted it out. I finished and got my degree. And then when I got out of school, I got a couple job offers and didn’t really like them. I almost got a job offer from Apple Computer, which I probably would’ve taken, as an engineering software evangelist, but I didn’t get it. It had come down to two people. So I didn’t get that and I didn’t really know what to do. Ron was out in LA and he was just starting to break into the business and get his first gig. He said, “Come and be a screenwriter!” And I was like, “… That sounds great!”

It was literally that much thought.

I’ve been studying sci-fi history, and it seems that many major influences in the genre tend to happen in groups. For example, in Brooklyn, New York, you had the Futurians and over here in LA, you had The Group, with the likes of Ray Bradbury, Richard Matheson, and Charles Beaumont. It’s interesting to note that such groups happened in the TV science fiction world with you, Ron Moore and the team you worked with. So, Ron talked you into coming out to LA?

It wasn’t that much of a talk. Ron had kind of slept on the floor of our first friend in his apartment when he came out here. Ron had a year or two in on Star Trek at that point. So he was kind of getting his sea legs under him, and I slept on his couch for like eight weeks.

My parents were sweet. They were so supportive. They thought I was deranged, I’m sure. I threw a few suitcases in my car and said, “All right, I’m gonna go and be a screenwriter!” And I think that they thought that I would get this insanity out of my system. I was still young. I had gotten my Ph.D. when I was 25. Anyway, it stuck apparently. My mom told me years later, when they were waving goodbye from the house, as soon as the car drove away she burst into tears. She thought I was throwing away my education. So that’s how I came out to LA.

How’d you break into Star Trek?

Star Trek: The Next Generation at that time was unique in the business because it had what was an open submission policy. So if you wrote a script and signed a release, you could get a script in the show. That’s what Ron had done. He wrote a spec script and his girlfriend knew somebody who worked on the show. And so she was able to get it to that person, and they read it and they liked it. It was one of those things that happened at the right time because he had gotten hired from that script and then I had come out.

I wrote a Star Trek spec, Ron got it to those people, they read it—and I got an internship with the Writer’s Guild to be an intern on the show. It was a great training ground. It was only six weeks, but I got to be in the room and break stories and made a little money. And then, because of my background, there was a position that Gene Roddenberry had created on the series, which was a Science Consultant. He felt that the original series had played really fast and loose with science, and he wanted the new show to have much more grounding in that respect. So, there was a guy that they were in the process of replacing and they said that I’d be perfect for the role.

So, I actually became a Science Consultant on the show after my internship, and that kept me around. I pitched some story ideas and then about a year or so after I’d been out to LA, Ron gave me a big break and said that he’d like to write an episode with me, and that went well. And that led to another episode of the show. And I think in less than a year after that, they asked me to come on as staff.

So I wrote a bunch of freelance episodes in year five and was on staff in year six and seven on the show.

What was the transition like when Star Trek was ending and you were looking for your next gig, did you find one instantly? Was there a dry spell?

I was the most junior member on staff on Next Generation and what happened was, Deep Space Nine was starting up and a couple of the guys went there. And then Voyager was just starting up too. Brannon Braga went there and it had a very small staff initially and I kind of got left off the roster.

That must’ve hurt.

It hurt at the time. I understand in retrospect why. But honestly, in retrospect, it was probably one of the best things that ever happened to me. Voyager was its own universe, and it was a very hermetically sealed universe. There weren’t a lot of connections between physical production and the writers. The writers kind of kept to themselves. There wasn’t a tremendous amount of back and forth. I was out of work for maybe six months or so.

My next gig was on a show called SeaQuest DSV, which was Steven Spielberg’s big science fiction spectacular. I was on the last season of that, which by then the series had already been reinvented three times. It was disastrous and it was also a great learning experience. I met some really good people there. After SeaQuest, I went onto The Out Limits, and that was a really good experience. It was Showtime's version or a remake of the original.

So back then, in the 1990’s—when you were going out for writing roles in television, were you pigeonholed as a sci-fi writer?

Absolutely. At the time, science fiction was a weird little ghetto. It was really a slap in the face coming out of the Star Trek camp. This was like the mid-nineties. It was not considered to be anything other than its own weird little thing. It was off to the side, it wasn’t mainstream television. Nobody wanted to read a Star Trek script. You couldn’t even use it as a sample.

You couldn’t use it as a sample?!

No. It was its own weird universe and it had all this weird space shit in it. Nobody even wanted to read it. My agent said, “You’ve gotta write something else right away.” It was a really strange thing—that show was just as much fantasy as it was anything else. It had some science elements, but it wasn’t really driven by science, it was driven by allegory. The funny thing about it is that if you really look at it, in some sense, it was a superset of other shows because within Star Trek you could do anything. Murder mystery, a legal drama, a morality play—and it wasn’t recognized for that.

How did you get out of being pigeonholed? Did you write different genre pilots? Did you decide that it was your strength and you were going to go with it?

What happened was, the first gigs that I was able to get were in science fiction because I wrote for Star Trek. I got hired on SeaQuest because Next Generation was a big success. They wanted that kind of success and quality since SeaQuest was struggling, even though it was on a network. So they tried getting some people from Star Trek on board.

Y’know, that show was another great learning experience. I met a really good friend, Javier Grillo-Marxuach. He did Lost, he created The Middle Man. Great guy. Great writer. We were the most junior members on that show. But that show was cool because it was the first really high-end computer effects driven series on television. It was so far ahead of its time, this was like 1996. We had the entire effects department of what was then Amblin Imaging, which later became DreamWorks. An entire effects department was working on it—the show was state of the art. We were on Avid, we had full animatics, in-house storyboard development. It was really smartly produced.

So, now your agents are realizing you’ve done sci-fi, you’ve been successful at it—obviously, those were the opportunities you were getting. Was there an urge for you to break out of sci-fi?

That was actually my own sort of analysis of the business. What happened after SeaQuest was that I went ontoThe Outer Limits, and that was a terrific experience because most people don’t actually get to have the fun of working in anthology television. And that show was a one-hour anthology. So, week to week, it was a Western show, a spaceship show, a present-day show—we would just bounce around all over the place. It was like making a mini-pilot every single week because you have to start from the ground up with production design, concept work, story, all the way through finishing, editing, effects. And it was one of the best workshop experiences you could ever have because it exposes you to every aspect of the business—and I got to do that very early in my career. And that’s what I meant when I got kicked out of the Star Trek nest, I was exposed to an entirely different level of filmmaking. And it made me a much better producer.

I know on that series, you got to work with Harlan Ellison.

Yes, it was on an episode titled “The Human Operators.” It was one of those classics of science fiction, which was co-written by Harlan Ellison and A.E. Van Vogt.

Harlan Ellison

What was it like working with Harlan?

That’s a good story. Every year on The Outer Limits, we tried to do an adaptation of a classic sci-fi story because the format of the show really lends itself to it. It’s really the dramatic equivalent of a short story. And I had loved Harlan Ellison’s essays for years. He’s probably one of the best essayists this country’s produced.

He’s phenomenal.

Phenomenal. Phenomenal writer. So, I had also heard all the terrible Harlan stories of how he would rant and rave about how City On the Edge of Forever got fucked up and every experience he had in television was bad—how he hated everybody. So, of course, I was terrified of him. Anyway, we arranged to get the story for The Outer Limits, and I remember my first phone call with him—I literally said, this is probably pretty close to the first words I said, “Mr. Ellison, I just want you to know from the beginning, that I’m far more interested in having your words on screen than mine.”

And he said, “KID! We’re gonna get along great!”

(Laughter)

And it was a delightful experience because I think with Harlan it was just an acknowledgment that the author’s and the writer’s work was primary and that it was the original piece that this was coming from. And I had given that to him—and it was genuine. I wasn’t trying to kiss his ass. I said, “I want to adapt your story because I think it’s a great story.” And I think that meant a lot. And he’s been very friendly ever since—and the episode won a WGA award.

Walk me through what happened next in your career.

Okay, so I left The Outer Limits after three years to do Farscape, which was down in Sydney, Australia. Again, another amazing experience. That show was this crazy operatic experience. Beautifully produced, and shot. It was a chaotic environment, but it was hard to make an American network level television show in Australia at the time. It had a great crew, great people, wonderful actors—David Kemper who was the showrunner was a mad genius with an incredible imagination. The show was quite unique and beautiful. Actually, I felt that the show was way ahead of its time in terms of serialization and the long dramatic arcs it presented in a science fiction series. I feel that that show would do much better today than it did back then. Also, it was on the Sci-Fi channel, which honestly at that time was backwater. They didn’t know who they were, what their identity was, what their programming was—they didn’t seem to like science fiction that much. And—um, I left that show at the end of season two. And at that time it was one of those moments where I realized I can either be completely pigeonholed at this point in my career, or I can try to branch out.

So I made a really conscious decision to branch into more mainstream stuff. And that was when I started doing cop shows and other stuff, which ultimately ended up getting me in the door on CSI.

What was that decision like, was it tough? Were you becoming bored with the genre fare because television wasn’t taking the sorts of risks that it’s taking now?

I don’t recall analyzing it that way. I was looking at in more in terms of—how do you continue to develop as a writer in this business? At that time, this was 2000, 2001, 2002, if you think of the shows, like great dramas, and I gravitate towards drama for the most part. The shows were like, ER, The Practice, X-Files, obviously a little genre, but more mainstream. Those were the shows I liked. NYPD Blue, beautifully written, intelligent and that kind of show, for the most part, didn’t seem to exist in science fiction.

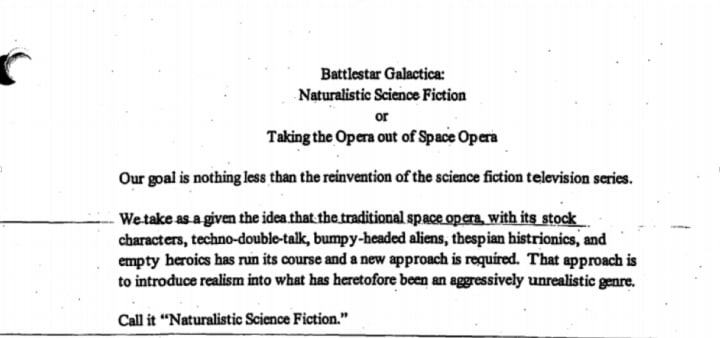

One of the things that Ron was always trying to do with Battlestar Galactica was with his manifesto that science fiction has to grow up. And he was right on. Characters and material were not being treated as well as other better genres were treating them. And if you survey the lay of the land at the time, at least for me—and again, these are very broad generalizations, I’m sure there were exceptions. But if you really want to dig into the best of what was on television at the time, it wasn’t going to be a science fiction show.

Excerpt from Ron Moore's Battlestar Galactica Series Bible.

You never worked on Battlestar Galactica, why is that?

No. I didn’t, I wish I did. I was on CSI—and I was on it for eight years. I was running that show and loved it. And on the last season of Battlestar, Ron asked, “Do you want to write a Battlestar?” And I said, “Fuck yeah I do!” And I remember having this conversation with my agent—“Ron wants me to write a Battlestar—and I want to do it!” There’s this long pause and my agent goes—“So you want me to ask Leslie Moonves to allow the showrunner of the number one show in the world, that’s on his network if you could write an episode of a show for Jeff Zucker on NBC?”

And I go, “Yeah!” He told me, “Shits not gonna happen, man.” (Laughter) So, there ended my dream.

Wow, that's too bad.

I often use Battlestar as an example when people ask me what shows I like. I think it’s a magnificent show. I really do. No show is perfect, and you can point to flaws. But what it was trying to do and what it accomplished and the level at which it was able to tell the full story—it was really quite wonderful and really deserving of all the accolades that it garnered.

Talk about the transition going from writer to producer to showrunner.

Showrunning is a weird job. You have to do a lot of things and not everyone makes that transition. It’s a strange combination—you have to be a strong writer, but also a creative visionary. You have to run a break, you have to manage people, you have to be comfortable with the technical side. It’s an odd sort of left-brain, right-brain combination. And I think, partially my own tendencies, even from the academic years, probably lent itself to it. I had both sides going a lot of times. I’m certainly not afraid of the technical part of it, and I’m certainly not afraid of the filmmaking part of it. And that’s usually where writers kind of get a little at sea sometimes. And also I’m lucky enough to work with people who threw you into the production side of the business, which happens a little less frequently these days. And I think it’s to a detriment because people will start running their own shows and they have no idea how the filmmaking side of things work.

Showrunning in television is kind of like being a director in features. I think that’s why you often see a lot of showrunners directing. They direct their own shows and then they make the transition to other things.

For me—I guess I was on that path. You can usually tell who the people are that have that kind of ambition. The staff that we had on Next Generation, even from the earliest days, the naked ambition of the four kids of that staff, Ron, myself, Braga, Echevarria.

Naren Shanker (far right), Rene Echevarria, Brannon Braga, and Ron Moore.

All we would talk about was how we were going to murder the boss, and when we were running things how shit would get done right. That was a common conversation, maybe that was just particular to our group.

Another joke on Next Generation was that if you actually had a holodeck and a replicator, you’d never leave your fuckin’ house. It would be the end of civilization, not the beginning of space exploration.

Talk about the difference between showrunning a television series of other genres, versus a science fiction series. What are the peculiarities?

Um—y’know, the writers' room dynamic on any show is unique to the personalities involved, and every show has its own challenges. CSIwas really a classic crime-mystery story, those could be extraordinarily difficult and complicated to break. Science fiction shows, depending on what they are can have all sorts of levels of peculiarities. I mean, take The Expanse for example. Because of the way we decided to have real physics or sort of a more accurate portrayal of space, there came a whole raft of physical issues that we deal with both on the page and in production, but every show is its own unique thing. None of them are easy, to be honest, but your emphasis goes to different places depending on what you’re trying to make. I think that’s probably the easiest way to describe it.

When you were coming off of CSI and eventually coming aboard The Expanse, were you conflicted about your return to science fiction? Was it the material itself, versus a desire to return to the genre?

It was a little bit of both. After CSI, I had done cop shows and more mainstream stuff for about ten years. I would get questions from agents asking things like, “Would you consider doing genre?”

And I'm like, “Dude, I love genre.” It was something I really wanted to do after CSI. One of the things with crime shows and especially shows of that nature is that you can get desensitized to the nature of murder and loss. One of the things I didn’t like about CSI is that as the show got on, year after year, it became a behemoth of a show, and there were a lot of big personalities on the creative side in particular. Even more, there was a tendency to sensationalize and fetishize blood and gore. And for me, what I liked about the show in the early years was that it was a unique way of doing a crime drama. The way one of our consultants described it was, “We need people on the worst day of their life.” And that I felt was quite beautiful, but as the show went on it became more and more disassociated from the reality of murder and loss, and more interested in the fetishization of blood and gore in a kind of high-style way.

It’s very digestible as entertainment and very fun, but kind of wears you down after a while. So when I came off the series, I decided that I wanted to go back to genre. I want to tell a different kind of story. Ron and I actually tried to reboot the old 60’s series, The Wild, Wild West with CBS, but we couldn’t quite get it off the ground.

So, now you’re serving as a showrunner for The Expanse. I understand that one of the things that appealed to you was that space is a character, the physical laws of nature is a character. Describe the challenges of expressing science in dramatic ways.

Yeah, on The Expanse, we try as much as humanly possible to make things real or realistic. But what we cheat all the time is the length of voyages and distances, because those things are impossible to compress, or to express in interesting ways dramatically. Game of Thrones does the same thing. Six months of walking across Westeros in the book is like a CUT.

We're guilty of the same thing. We try not to focus too much on how long it takes to get from Mars to Jupiter because the answer is it's pretty fuckin' far. (Laughter) Even if you've got a great little fusion drive that can get you there. It's one of those things in the novels, where they discuss the length of time and go, "Okay, great, pass the spaghetti." It's really easy to get around, that doesn't work in a television show.

So in that aspect, we cheat. BUT, when it comes to gravitational effects, thrust gravity, spin gravity, when the ship turns off its engines and everyone becomes weightless—that stuff we try to treat as realistic as possible. It goes back to that space is a character thing. The genre runs away from it and it always has—the one movie that got it right was 2001, and that movie was made in 1968.

It's also an awful date movie, as I once learned in college.

Oh, my goodness. Or, the perfect date movie if she likes it as much as you do.

That's true. My current girlfriend likes 2001. Ergo, she's a keeper. So—where are you guys right now in production?

We are in script for season three. We are writing madly. We start shooting our first two episodes starting on July 12th. So we are right in the thick of it. Yeah, we've been working for the last couple months, and things are well under way.

The Expanse has a lot of characters. Is it challenging to toggle between so many different players? How do you handle that as a writer?

It’s a tricky balance. It’s a particular kind of storytelling; you do see it in Game of Thrones. The decision to do that honestly was because space is really big. The storylines were affecting people in these widely disparate far-flung places. And so, the approach dramatically, was to give each character and storyline a piece of the puzzle, but only the audience is getting the whole story—so what it necessitates is you have to be aware of the interaction of those storylines at all times. And you have to focus on what your characters know in a particular place and what they don’t know and yet use all of these elements in concert to tell a larger story to the audience at any given time. That is a kind of specific complexity to The Expanse. The show is dense, there’s no question about it. It’s a complicated show. It’s highly bingeable, but you gotta be paying attention.

One quick little story about The Expanse if you want to hear it—When I was originally sent The Expanse, my agent goes, “Hey there’s this new show, I want you to take a look at it.” I took a look at the email and I saw that they were setting it up at the SyFy channel, and I hit trash. I literally hit trash. I didn’t even read the email any further.

Why?

I had hated their programming for such a long time and I found them very frustrating. After Galactica they had made nothing that I liked. And every year they’d send me projects and they were always bad. I didn’t like it all. I just threw the email away, I didn’t want to work for them. Then three weeks later my agent emails me, “They really want you to read the script. Would you please read the script?” And I said, “FINE.” So I scrolled down in the email and I didn’t know it was based on a book, but I saw that the pilot was written by Mark Fergus and Mike Osby, who had written Children of Men, which is a movie I love. Beautiful movie. So I read it and called my agents and said, “This is not the kind of stuff that they’ve been making in a very long time.” The intent was to make it at the right budget level, and it was a very different type of show for SyFy.

So I said, “Yeah, I’ll take the meeting.” I went and hit it off with the whole bunch of them and that was the beginning of it. What had happened was that The Expanse was the first big play that they made when Bill McGoldrick when he came over from USA. There was a whole other regime that was pushed away. That was a problematic regime. SyFy Channel didn’t really understand its identity. There was no reason TheWalking Dead, or Breaking Bad, or any of these shows couldn’t’ve been on their air. They were all on the same level. SyFy had a much higher profile than AMC or any of these networks, and yet they had missed the boat because they had turned their back on the very programming that their audience wanted.

It’s in their name!

It’s in their name! So, when Bill McGoldrick had brought his guys over, and I knew Bill from some other development stuff and I really liked him. When I understood that they were serious about this, and they really wanted to make this, and it was straight to series, which was a really big deal because it allowed to tell the story in a different way than in doing just a straight pilot. I thought, okay, this is an opportunity to make something that I haven’t really seen before. The book had a very interesting quality in how it expressed life in space and it wasn’t doing cheap silly stuff that can easily come in this genre if you aren’t taking it very seriously. And it was a very smart, thought out world. The authors Ty Frank and Daniel Abraham, who are actually James S.A. Corey, had really done some beautiful work. And Mark and Mike wrote a beautiful pilot. And the guys at Alcon Television wanted to make the show for real.

Andrew Kosev and Broderick Johnson are the co-ceo’s of the company. They are really old time independent producers. They are hands on, they love the genre and Sharon Hall who was the president of Alcon Television shepherded The Expanse like it was her baby. I worked with her before at Sony Television. It was the right group of creatives. They put together an amazing visual effects team. Bob Monroe was our visual effects supervisor, they wanted to do everything right. And they trusted their creative to tell the story in a particular way and because the studio was financing the show it gave me the ability to say, this is how we’re going to do it. And so, with all those elements, I thought, okay, I can make this into something pretty good since there is a good infrastructure in place—and here we are in season three.

Is there anything you'd like to express to the larger science fiction community or fans of the show?

Y'know, maybe one thing. We were touching about it a little bit, regarding the ghettoization of science fiction. One of the interesting things that I saw over my career going from those early years when no one would read a Star Trek script till now—I remember the conversation I had with the people at Bruckheimer Television. They were producing CSI and launching another show, and they said, “Y’know what we need? We need one of those Star Trek guys. One of those science fiction guys to run this show.” Because what they had realized is that people who had come out of that school had really good story discipline and really understood a lot of the different genres, and they could bring those skills to work in a very broad way. So what you saw was a change in perception of the business with respect to the genre. And I don’t think we have anything like that kind of ghettoization anymore. I think people move very freely between all these sorts of different things because a good writer is a good writer. And good storytellers are good storytellers, and it’s not a little garden walled off to the side. It’s part of this very broad landscape, and I think it’s very nice to see this change of perception in that part of the industry. I think it’s a great time for science fiction in television right now.

It’s never been better.

Outside of The Expanse’s continued success, what do you want out of your career at this point? What do you want out of your writing and your legacy?

These days, honestly, I like shows that have something to say. I like shows that can tap into culture or events. We get a lot of questions regarding our series—“Oh is this a direct political allegory, or a look of this in our world in your show?” And some of it is, though, a lot of it is just the sad way that human beings recreate their history over and over again in every era. But it’s nice to have those resonances when you can actually become a part of the cultural conversation at any given time. CSI was able to do that, Next Generation was able to do that. It’s nice when that happens. At this point, honestly, I’m just looking for things that speak to me in one way or another.

Regardless of genre?

Kind of regardless of genre. This is a question my agents ask me and its drives them crazy when I answer—“Y’know, I just want to make something good.”

About the Creator

Joshua Sky

Originally from Maui, Hawaii, Joshua is a multi-award winning writer based in LA. He has written for Marvel, SciFutures, Motherboard, Geeks and is represented by Abrams Artist Agency.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.