Science Journalist Lee Billings On Life Beyond the Solar System

For those just mad enough to prepare for a strange new future of super-Earths and ice giants, we propose Lee Billings' 'Five Billion Years of Solitude.'

The history of science can be read as a series of brusque reality checks. Once, we imagined ourselves the center of a small and harmonious universe, gifted with a sun content to revolve placidly around the Earth. In time, however, our real estate was relegated from the center of everything to a hum-drum corner of an unimportant galaxy in a much bigger and more tumultuous universe. Upon closer inspection, our sun was revealed to be just another star, born from a nebula, fated for eventual collapse. At the same time, we came to understand the spark of life, transforming in the process from the mini-gods of a pedantic little empire into nothing more than a consequence of biological randomness.

Again and again, we have found our sense of centrality challenged. The more we learn about the nature of the universe, the more we discover that we are, at best, stowaways on our own ship, peeking out of a porthole into an elegant, impossible strangeness. We are a fortuitous coincidence; That truth, if you really sit with it, could drive you halfway to madness.

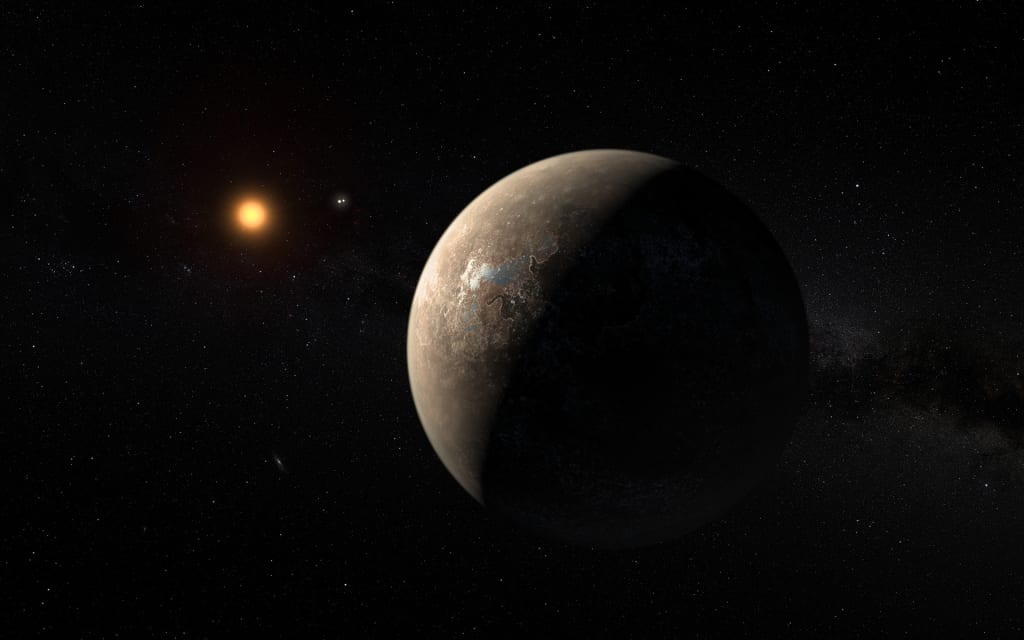

One form this madness takes: the impulse to search the universe for habitable exoplanets, proof that we might not be alone. Exoplanetology is a unfolding revolution, a hybrid science which calls for many different disciplines—theoretical biology, astronomy, planetary science, geochemistry, geology, astrophysics—to be bound together in the deeper study of extrasolar worlds, with all their manifold implications and seductions. Over the last few decades, so-called "planet hunters" have discovered thousands of new worlds in this manner. It is a particularly poetic gesture, and one which will undoubtedly define the next major reality check in store for our species: whether or not the universe, somewhere in its inky reaches, has nurtured life other than our own.

For those just mad enough to prepare for this strange new future of super-Earths and ice giants, we propose Lee Billings' Five Billion Years of Solitude, an exceptionally lyrical book about the quest for life beyond the solar system.

Pop-science books are a dime a dozen these days. The din in the marketplace is often distracting enough to send writers (and their publishers) scurrying for soundbites meaty enough to sate an idea-hungry cultural appetite. To his great credit, Billings takes the opposite tack. He lingers gracefully on quiet stories, makes nuanced speculations, and takes time and care to unravel the things which deserve time and care. He is also, not insignificantly, a wonderful writer, gifted with the capacity to ground even the most esoteric of scientific speculations—something our interview below should amply demonstrate. Each time his subject matter drifts into a far-flung corner of the universe, or the cosmic scales at play start to strain your capacity for imagination, he snaps you back to Earth with profoundly human stories—of the people who hunt for these elusive planets, their passions, loves, and—above all—their fortitude in the face of mystery.

Claire Evans: A simple one to start: why care about exoplanets?

Lee Billings: This is a case, I think, where the conclusions of science mostly confirm intuition-based "common sense" that is already deeply embedded in the human psyche. Simply put, we live upon a planet, and so when we think about life elsewhere, we tend to assume it at least started upon a planet, too, even if that life somehow ends up leaving planets behind. If you can dream it, a planet somewhere out there can probably be it, and that’s a compelling, seductive idea.

The nascent science of astrobiology has come up with a wealth of corroborating evidence that planets and perhaps their siblings—moons, asteroids, and comets—are the default cradles for life in the universe. These objects seem to be the only things nature makes that can be experienced as "worlds." It's hard to imagine some form of life arising and persisting in the photospheres of stars or in the frigid depths of giant molecular clouds. And, based on our present grasp of physical laws, one can't simply voyage between stars or jaunt across the galaxy in the same way one might walk between houses or travel to another continent. Planets seem to be at the intersection of all things great and small.

So if you care about life or the experience of living in "the world," what that really means is you should care about planets—whether our own or others, whether around our star or others.

So they appeal to us emotionally, as worlds. Is that why exoplanet hunters dedicate their careers to searching for them?

I can’t really speak for all the planet hunters, but other than the opportunities that worlds harbor for life, planets are fundamentally interesting because of their diversity. There seem to be more permutations of possibility, more varieties of experience, available upon planets than for any other astronomical object. Our robotic reconnaissance of the solar system has revealed that no two planets around the Sun are extremely similar. Each one has its own distinct history and character which cascades down into even more environmental diversity: Consider the oceans of Earth, the immense mountains and canyons of Mars, and the rich assortment of moons and rings around Jupiter and Saturn.

Looking out to other stars, we're finding lots of planets and planetary systems for which we have no familiar local analogs, and really we've barely begun searching, so there's lots more diversity to still be uncovered. We're finding hot Jupiters, warm Neptunes, super-Earths, and free-floating worlds unattached to any star. We're finding what may be carbon planets with diamond continents, ocean planets with nothing but water almost all the way down, planets made of pure iron and planets less dense than Styrofoam, and so on. So as immensely diverse as our own planet and planetary system is, that seems to represent only the slimmest fraction of actual planetary diversity. All that means planets offer a wide open space in which the mind's speculations and nature's experimentations can run wild. If you can dream it, a planet somewhere out there can probably be it, and that's a compelling, seductive idea.

One of the defining qualities of your book, I think, is how it moves between massive scales of both distance and time. You cover the formation of the universe, geological history, the ultimate fate of everything—as well as the short-term pursuits of scientists. In writing the book, were you mindful of these leaps between micro and macro?

Yes. Weaving human stories into discussions of our planet's formation and of life's evolution is a way to convey that we are all part of one continuum, that we are all potential players in a greater, grander narrative. In the book I talk about great transitions in the history of the Earth, events such as the formation of the Moon, the oxygenation of the atmosphere, the rise of complex multicellular organisms, the colonization of land by plants and animals, and the extinction of the dinosaurs. Right now the Earth is unquestionably in the midst of another great transition, though this time the driving force isn't an asteroid falling out of the sky or a spate of erupting supervolcanoes—it's us.

But unlike the dinosaurs or the trilobites or all the other organisms that were largely powerless during past transitions, we seem to have a choice about what will happen to us and to our world. We can choose our own adventure, or we can author our own disaster. We are truly becoming the masters of this planet, whether we're ready for that responsibility or not.

Most of the Earth's past great transitions unfolded relatively slowly, over millions of years. The one we find ourselves in today, however, is occurring within the span of a few generations, yet it still carries the very same long-term implications as all those that preceded it. I'm both awestruck and terrified by the fact that our actions, in aggregate and in some cases even individually, have the potential to echo down through the eons, through the remaining time left for life on Earth—and even beyond.

Does our desire to move outwards and explore the Universe redeem us at all?

I certainly like to think so. A lot of people who dwell on these matters today view the collective effects of human activity in almost entirely fatalistic terms. I believe it’s important to cultivate the possibility of more positive outcomes by acknowledging the human capacity for transcendent greatness. We can be cruel and terrible, yes, but we also seem to be the most powerful potential reservoir for loving kindness that Earth’s biosphere has ever produced.

When you are faced with the outlines of how our planet came to be—how it came to life, and life’s slow, stumbling progression from single-celled simplicity to us—you begin to realize just what a strange and wondrous thing it is to be alive and to possess any awareness of anything at all.

It is at the very least plausible that we are presently the only technological civilization in the entire Milky Way. It could even be that no other living planets exist in our galaxy or throughout the rest of the observable universe. We don't know the answers to such questions—yet. But imagine for a moment that we are essentially alone, and that we never manage to sustainably expand out beyond our little lonely planet. So instead we just die out, and the Sun cooks most of the surface biosphere in a billion years or so, and our star burns out several billion years after that, and that's it, that's the end of Earth’s story. I can think of no greater tragedy in the universe than for a solitary point of life and hope succumbing to existential apathy when it could have filled so much empty, unthinking space with beauty and joy and meaning.

This was something the pioneers of the Space Age keenly realized, and a yearning for transcendence colored everything they did. They wanted to build bridges to the stars, and they knew they didn’t have forever to do it. Today, national space programs tend to sweep that transcendent urgency under the rug, and that’s probably because most of their constituents—most of us—live lives of blissful ignorance, unaware that we all dwell in deep time during what may be a fleeting era of miracles.

In researching and writing this book, you spent time with people who have, as you write, "a serenity that suggests awareness of one's inescapably small place in the world." How did your perspective on your own life change?

In the thick of it, I found myself oscillating between depression and euphoria. I’d get depressed realizing that all these brilliant, passionate people might never find other Earths and extraterrestrial life. I’d get depressed thinking about the seeming futility of everything, how our time is limited, how perhaps nothing really matters on both personal and planetary scales. Then I’d get euphoric about the possibility that I might be wrong.

I had strange recurring dreams while working on certain chapters. In one I was always in a panic, digging in the ground beneath a red sky, looking for something I could never find. My fingers would close around objects in the dirt and I’d pull them out into the light, but I could never tell what any of them were other than that they weren’t what I was looking for. It was good to wake up from those.

Sometimes, thinking about the geological past and future of the Earth, I’d be hit with a disturbing sense of unreality that was hard to shake. I would suddenly feel entirely insubstantial, and I’d have to get up and just take a long walk with my dog around my neighborhood, trying to ground myself. I spent a lot of time just listening to the wind rush through the trees, feeling the sunlight or the rain on my skin, taking in the slow changes of the days and seasons.

When you are faced with the outlines of how our planet came to be—how it came to life, and life’s slow, stumbling progression from single-celled simplicity to us—you begin to realize just what a strange and wondrous thing it is to be alive and to possess any awareness of anything at all. So, yes, we are all inescapably small parts of a much bigger picture, but compared to most everything that has preceded us on this planet we have what amount to god-like knowledge and power. That sort of heightened awareness, at its worst, leads to a terrible solipsism and selfishness. At its best, it allows a more mindful engagement with the world.

Exoplanets are so distant that they often border on being simply intellectual. Do you have a sense of their reality?

Yes and no. The fact is, we have an intimate sense of the Earth, and the Earth is an exoplanet to every star in the sky save for one. It seems so prosaic as to be almost pointless, but if you want to know what life is like on a habitable exoplanet, just look around you. If you want to meet a mysterious alien, go watch birds or insects or fish or trees or paramecia. Go look in a mirror. That’s obviously a bit of a cop-out, but it’s part of this broader mindset that we and our planet are part of this larger cosmic continuum. Our experience here on Earth is of great relevance to our search for habitable planets, life, intelligence, and technology beyond the solar system, if for no other reason than that we must begin by searching for those things that we can hope to recognize.

Even if a human being someday stands on the surface of an exoplanet looking around, having traveled to it in some epic interstellar voyage, it will be all too easy and almost inevitable to project our own desires and dreams and past familiarities onto these strange new worlds.

But, as I mentioned earlier, it’s already clear from the data in-hand that what we see around us in this world and in this planetary system is just one isolated instance from a much more diverse ensemble of possibilities. On the bright side, the laws of physics and chemistry and thermodynamics seem to be the same whether on Earth or on the other side of the universe, which means we have some hope of gaining a better understanding of what all these weird alien planets are actually like. So we are already doing things like sniffing the atmospheres of a handful of big, hot exoplanets, seeing what’s in their air, even very crudely mapping their atmospheric circulation patterns. And hopefully in the future we’ll extend those same sorts of techniques to smaller worlds in more clement orbits, worlds that, based on all we know, offer better chances of harboring life that we can detect.

Do you think we can ever be objective about something as central to our consciousness as life, and the potential of its existence elsewhere in the universe?

I’m not sure. I spend a great deal of time in the book with a man named Greg Laughlin, a remarkable astrophysicist who does a lot of exoplanet-related data analysis at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Laughlin was one of the early boosters for a dedicated effort to look for small rocky planets in Alpha Centauri, our Sun’s nearest neighboring star system. I asked him once via e-mail, years ago, if he ever dreamed about the environment of a habitable planet there. Alpha Centauri is a triple star system, so I was expecting a reply where he’d talk about things like the weirdness of having multiple suns casting different shadows on the ground. Instead he just sent back a quote from a science-fiction novel, a snippet which he wouldn’t elaborate on any further. I was puzzled at first, but the more I thought about the quote he sent and the context, the more I understood what he was indirectly saying. Even when we have the best data available, even if a human being someday stands on the surface of an exoplanet looking around, having traveled to it in some epic interstellar voyage, it will be all too easy and almost inevitable to project our own desires and dreams and past familiarities onto these strange new worlds in a way that’s not necessarily scientific or rational at all.

As a science writer, you're regularly tasked with the duty of suffusing arcane and dry subjects with life. You are exceptionally talented in that department. How do you go about creating a balance of facts and poetry, without tipping too far in either direction?

I feel very strongly that any sort of “poetry” must be somehow earned, because otherwise it will be perceived as pompous and stilted. I try to earn my more flowery moments through diligent in-person reporting.

For me, access really is everything. I’m not a scientist, and I don’t consider myself an expert in many things. What I am is a conduit, a catalyst, and so I work best when I’m connected on personal and professional levels with engaged and patient experts. Ideally, they keep me straight on the facts, and in the process their own words and their stories as I understand and interpret them help shape any flights of fanciful prose I undertake. That doesn’t necessarily mean I take everything they say at face value, or implicitly trust them in all things—you have to balance becoming friendly and familiar with someone with the need to maintain an appropriately savvy journalist-source relationship.

I know I’m in a good place in any of those relationships when so many serendipitous and resonant and poignant moments begin to unfold that I start worrying about how I’ll manage to do justice to any of them. That’s when a bit of poetry tends to slip in.

What value does beauty have in science?

That depends on your definition of “beauty.” Is beauty simple or extravagant? Is it orderly or chaotic? Which is more beautiful—the obvious or the hidden? Is something beautiful by virtue of being a rule, or by being that rule’s exception? Is there more beauty to be found in a lofty theory, or in a well-crafted observation? I ask these questions because I don’t know the answers.

In science, beauty is often associated with a thing’s ability to be known and understood, and yet some of the most beautiful things we experience—our consciousness, our subjective thoughts, emotions, and sensations—currently exist beyond the boundaries of science. The history of science is littered with theories and experiments that are beautiful in every respect but for their total failure to accurately describe or measure reality. We like to tell ourselves beautiful stories, but I don’t think that always makes them true.

What I admire about your book is that although it's finely researched and as ironclad an example of scientific writing as one could ask for, in the end, it's really a chronicle of many intersecting human stories—not just exoplanet hunters, but people like James Lick, the California land baron buried at the foot of his telescope. Why such an emphasis on people?

Well, the simplest answer is that science is, at its heart, a human endeavor. Scientists aren’t cold, unfeeling automatons—they are people just like the rest of us, and their actions are shaped by the same human desires and flaws that we all recognize. The humanity of scientists gets lost all too often in popular accounts of their great discoveries and deeds, and I didn’t want to make that mistake.

As for James Lick, his story has lots of interesting resonances with various themes in the book, and one of those is the idea of our actions unpredictably rippling out to change the world. Lick was a guy who made a small fortune building pianos. Then in 1848, when he was in his early fifties, with most of his life already behind him, he decided on a whim to move to California, which was not yet a state. He arrived in a quiet seaside village called San Francisco, lugging a chest filled with $30,000 in gold. He wanted to buy up Californian land on the cheap, in hopes that he could reap large profits if and when the US annexed the territory. About two weeks after Lick's arrival, a carpenter by chance stumbled upon gold in the American River, kicking off the California Gold Rush, which sparked the mass settlement and development of the western United States. Lick was flooded with sales offers from San Franciscans abandoning their land to go seek gold in the hills, so he bought up all the available land, and built an empire as California’s population boomed.

Whether through chance or fate, accident or intention, it is indisputable that from time to time lone individuals or small groups can have profound influence that extends past where they can presently see. Could that same potential extend out far beyond our little blue planet? I like to think so.

Lick became the richest man in California, and he decided to spend a fraction of his wealth building what was, at the time, the largest, most powerful telescope on Earth, establishing what would become Lick Observatory on Mount Hamilton. Lick Observatory is where the majority of the first exoplanet discoveries of the 1990s and early 2000s took place—it is arguably the “ground zero” of astronomy’s ongoing exoplanet boom. So in a sense you can trace our exponentially growing knowledge of worlds around other stars to a curious set of coincidences that all came together when a piano-maker had a mid-life crisis and decided to try his luck in California. Lick was in the right place at the right time, and the rest, as they say, is history.

I think a compelling argument can be made that everyone presently living on this planet is in a position roughly analogous to James Lick’s when he showed up in California hauling his gold-filled chest. We all find ourselves in a strange time, a turning point in history when the world is suddenly, profoundly changing before our eyes—and we have the power to control its course. We are all surfing on what may be the greatest transition in the history of our planet. A lot of what led to our being here in this privileged position to witness and take part in this transition seems to come down to a chain of chance stretching across billions of years, from before our planet formed up into the present day. That’s really quite extraordinary, when you think about it, and it makes me wonder whether humans can rationally hope to become not only a planetary-scale force, but something larger that operates at stellar—even galactic—scales.

Whether through chance or fate, accident or intention, it is indisputable that from time to time lone individuals or small groups can have profound influence that extends past where they can presently see. Could that same potential extend out far beyond our little blue planet? I like to think so.

What do you hope your readers take away from Five Billion Years of Solitude?

It’s my hope that anyone reading the book will come away with a sense that in the fullness of time we may be at the very beginning of our history. All that we've ever known may only be the opening act of a great story that begins but does not end upon Earth. What we do today and tomorrow may hold great ramifications for places and times very, very far away from us in the here and now. We could play a crucial role in shaping the future of our planet, our solar system, and perhaps even more, and I suspect that some of the critical actors in this unfolding story are among us on Earth today...Maybe I’ve even been lucky enough to profile one or two of them in the book.

Science journalist Lee Billings explores the past and future of the "exoplanet boom" through in-depth reporting and interviews with the astronomers and planetary scientists at its forefront.

About the Creator

Claire Evans

Claire L. Evans is the lead singer of the pop duo YACHT. She lives in Los Angeles.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.