The Watcher

From a lonely tower above, the watcher guards the city of wishes.

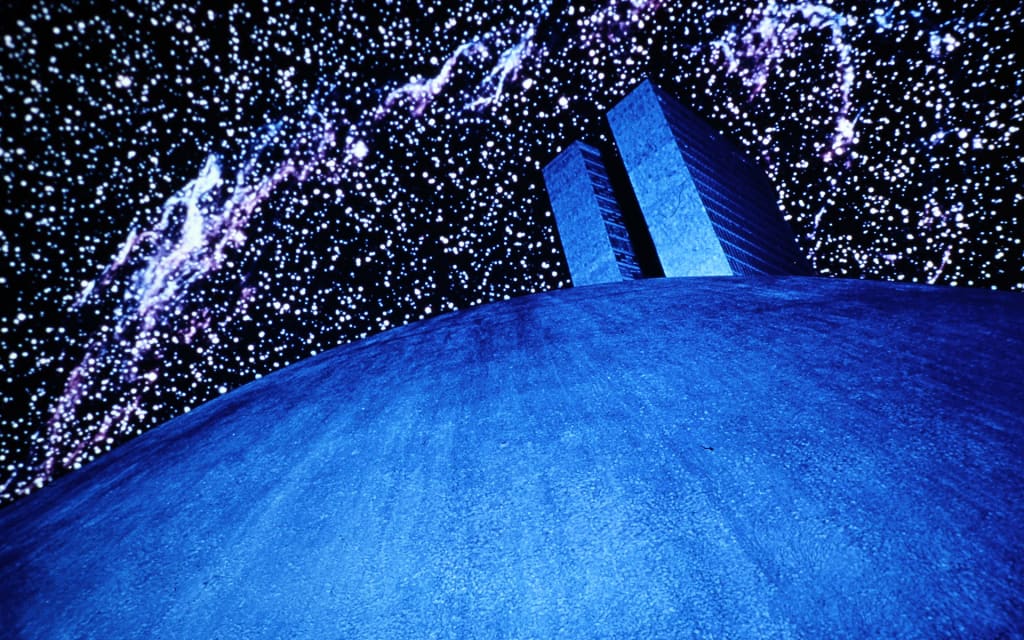

From the dome of his mile-long tower, peeking above the cracked earth of a former schoolyard, Dalen studied a wall of sulfuric storm clouds overshadowing the husks of Chicago’s skyline. One level below, a window wrapped around the tower’s shaft overlooked the hidden city, laid out like the layers of an onion. Were the city lifted to the surface, it would look like a giant toy top. The carved streets and homes lay open like a labyrinth, lit by cauldrons of engineered glowworms hanging from the cavern ceiling.

As Dalen ran his calloused hands over the railings of the tower’s stairwells, the lights in the cavern awoke, heralding a virescent dawn. The grooves in the walls transformed into waves in the morning glow, as if the city floated inside an oceanic bubble. From his monitors and through his telescope, he watched the city come to life—the stirrings of lovers, families eating breakfast, children walking the promenade to school, shopkeepers lifting the shutters to their stores, often displaying artifacts and photographs of a world above that no longer existed.

In the small apartment where he grew up, he could see his wife, Ora, getting dressed. She always fussed over the holes in her antique scarves, sewing them shut with twine. A picture of herself and Dalen, taken not long before he was called to the tower, rested on her dresser by the letter he’d left behind. It was taken on Wishing Day—not long after their son, Enoch’s, third birthday. They had wished for a child for years, and had all but given up when they found themselves, at forty-six, the parents of a baby boy (I wish for a long, healthy, happy life for my son/ I wish for my family to live long enough to see the sky). Ora brushed her hair, painted her lips with the homemade dye she used for lipstick, and said something into the mirror as she always did, the same few words, the same shape of her lips, the same four seconds. Dalen spent nights thinking about what those words could be: Where are you my love? Where have you gone? What are you doing today? But what Ora said everyday was: “How could you leave us alone?”

In the next room, Enoch did push-ups and sit-ups, trying to bulk up to impress a cute nursery technician at the hydroponics lab where he worked. At twenty-two, he still had his father’s spindly body, although his last growth spurt made him surpass Dalen by three inches. Dalen smiled at his son’s effort. But he knew that this part of Enoch’s life would soon be over.

He breathed in deeply as he watched his son, but immediately winced, as though his lungs were lined with needles. On recent nights, he’d woken feeling like he was drowning. Just as he was compelled to follow the images in his mind to the tower’s gate all those years ago, he knew, from the feeling in his gut implanted by genetic programming, that he only had twenty-three days, four hours, and seven minutes to live, to exit the tower like his father and his grandfather and die on the planet’s surface. This last matter, he supposed, was supposed to be a gift for the service provided by the men in his family—to die under the real sky after having been forced to live alone in the fake one.

Enoch stopped working out and stared into the mirror. His eyes widened, and Dalen realized his son was receiving the first of many flashes—numbers, passageways, doors, and always, always, the image of the tower. The colors:red, blue, yellow, yellow, green. Over and over again. He could hear his mother stirring in the next room but didn’t want to say anything. A weird head rush from working out, perhaps. He got dressed and yelled goodbye as he left for work.

Dalen squeezed a tube of nutritional paste into his mouth—beef stroganoff—that had an expiration date older than the city’s. People worshipped the watcher and the tower as a beacon of hope, and Dalen had, too, not realizing that the stones he threw as a child were being sent to his father, who he thought had died in an explosion at the heating plant. Teachers would tell stories of the ancestors, how the clouds had been set aflame, how families climbed down the tower, and how one man stayed behind to ensure humanity’s return to the surface. Wishing Day commemorated this descent and the dreams of the people. But apart from preventing breaches and monitoring life support, daily life in the tower consisted of watching and recording the world below—there was nothing better to do. At first, Dalen was fascinated by his vantage point. People having sex? Of course. Who wouldn’t? The women he secretly admired taking a shower? You bet. Late night brawls in the city’s undesirable quadrant B, meetings of radicals, boys playing soccer on the promenade, and even the occasional murder. In old journals and logs, Dalen read of previous watchers taking an all-too-interactive approach with their job, using the tower’s weapons to deliver swift justice, sometimes even killing people for sport. But Dalen had appropriated the rules left by his father: Look but don’t touch unless absolutely necessary. The world below is their own to rule. You are God now. You are the person people throw wishes to on stones.

I want to live long enough to drive a car. Specifically, I’d like to drive one without a roof, so I can look up at the sky like the cars in the old world magazines. I want to wear dark glasses and feel the wind in my hair.

I wish Colette and I had compatible work schedules. I wish we worked in the same habitation ring. I’d like to come home to her every day, and I’d like to tell her I love her in the morning.

Watcher, please let me live long enough to see my grandchildren grow up. I wish for the lights in the city to remain bright and strong for them. I wish for them to climb the tower and breathe in fresh air and feel rain on their skin.

Normally, Enoch would stop frequently on his walk to work, talking to old friends—the girl at the produce stand who gave him his first kiss when he was ten, the boy who used to live next door and now patrolled the corridors as an assistant constable, the lonely old man who sold tiny ice cream cones in exchange for stories and company. But this morning, the halls seemed to take on a life of their own. And without realizing how he got there, Enoch found himself standing in front of a mural in the innermost populated ring, one of the older designated areas for throwing wishes. The scene, “The Ascension of the Children,” was branded into every citizen’s mind by bedtime stories and early school lessons. It depicted seraphim helping people climb up the tower and the city as a seed, having sprouted roots leading to the surface where a sapling had broken through the soil. In a field, the founders and all the former mayors were depicted, smiling under a blue sky. The watchers of the tower? Absent.

At the hydroponics lab, Enoch tried to focus on work, but Talia had been smiling at him lately, and always chose a workstation next to him. He took a deep breath of the scented oil he imagined she dabbed on her body. A cluster of moles resided on her neck like the points of a star; he wondered if entire constellations were hidden beneath her clothes. Today would be the day, he thought. At lunch, he would ask her out—perhaps a picnic near the lightning gorge where the glowworms are cultivated.

“Are you going to any of the Wishing Day festivities?” she asked. “I hear the parade is going to be bigger than ever this year.”

“Maybe,” Enoch said. Oh, dear God yes, he thought. “Depends on if you’re going, I suppose.”

Being somewhat of a loner by nature, Dalen made the transition to complete isolation more easily than other watchers. His daily routines evolved from the day shift at the waste refinement plant, helping his son with homework, and massaging his wife’s back before bed, to hours of people-watching and reading the wishes on stones piled like cairns at the tower’s base. Before bed, he’d examine the video logs of other watchers, pore over the pages in their notebooks—their voices becoming increasingly distant, their handwriting less legible, almost indecipherable at times. “Trust your damn gut,” said his grandfather in the last recording he made. “Not these infernal machines. Hard to say when the city’s inevitable fall will become apparent, although I suspect someone has looked into the matter. For all I know we’re it. Maybe we’re all down here in the dark.” His great-grandfather recorded messages to his mistress that he could never send, watching her carry on with her life as he held on to the love affair they once had—“You always look so beautiful in that old, polka-dot pajama dress,” “The thought of never being able to hold you again has almost driven me mad,” “What must you think of me? Do you think of me anymore?”

But it was the entries of his father, Zeke, that haunted him the most, the only logs that he viewed just once and put away. Zeke described seeing his father’s withered body leaning against the dome outside when he arrived. “No rhyme or reason when your time is up in this place. Maybe the tower knows something about our bodies we don’t. Maybe they’re putting us out of our misery. It’s a special kind of hell in here, son. Everyday, I had to watch the rains eat at your grandfather’s flesh, the wind pull at his clothing until there was nothing left. I’m going to do my best to make sure you don’t have to go through with that. You’ll be up here soon, I expect. It looks like a nice day up there...looks.”

On the monitors, Dalen saw that a large rally had begun assembling just outside of the city walls. Young people dressed in black mostly. Some were the children of people he knew, young men and women he’d watched grow up. And then, as he scanned the city with his scope, he saw her: the girl his son had feelings for, the girl in hydroponics with a chestnut ponytail and freckles. She walked alone and took service corridors, following the markings on rusted pipes to guide her to her destination. She looked back to make sure no one followed her and then quickly changed into a black jumper she had in her backpack. “What the hell are you doing?” Dalen whispered. “What are you getting yourself into?” He averted his gaze to the rally, hoping to not find his son. And then to his home, where he saw Ora reading the letter he left...and Enoch drawing the maps forming in his head, trying to make sense of it all.

Just like his father. This was the resounding thought going through Ora’s mind as she read her husband’s last words, trying to convince herself that her son’s peculiar behavior—his late night walks to God-knows-where, hours upon hours locked in his room—had nothing to do with the deadbeat who left them and more to do with being in love, growing pains, male issues that her son thought she wouldn’t understand. But the letter suggested otherwise, and as she raised Enoch, she tried to forget that something different might be in store for her son, something that might take him away from her. There were just so many questions. Sometimes it was easier imagining Dalen dead, his body deep within a crevice outside of the city. Another woman? Was he living with another family in another district? Ora entertained the possibility for a while, but couldn’t imagine Dalen having the time or inclination. He’d be absolutely terrible at having an affair, she thought. He smiled like an idiot whenever he lied. She read the mysterious last few lines again, directed to their son: There will come a time when your life will change in ways you can’t even imagine. And when that time comes, I want you to hold onto all that you know and love and all that has made you who you are for as long as you can. Be brave. Be hopeful. Be my son. Ora put the letter away and heated dinner, calling to Enoch to come out.

Enoch began carving the city into the wooden platform beneath his mattress, noting numbers he associated with certain doors, colors with certain corridors. He wrote along the streets he carved in languages he did not know. Mathematical proofs and equations hovered over the gates of each circle of the city. As he carved, everything seemed to make sense to him, but the moment he stopped, he could barely believe he was capable of such a thing. But that he was being led to the tower was clear. On his nightstand, he picked up the communications code Talia had given him. Part of him wanted to call her now, tell her how he really felt, really ask her out this time. But he knew that the sickness in his stomach didn’t just have to do with calling a girl he liked. Outside, he could hear his mother calling. Enoch sensed she felt something had changed with him. But he didn’t know what to say, and more than anything, he knew deep down—for reasons that seemed more instinctual than anything—that he had to keep the nature of his daydreaming a secret.

I wish my husband and I could earn more credits, so we could give our daughter everything she wanted. I wish Ceric would stop calling me names at school. Also, I want be placed in the mechanics track next year, so I can help my dad fix things. I wish for a healthy boy. I wish for my wife to love me the way we she used to. I wish things were better at home. I wish the city had more medicine to give, so I could breathe better. I wish for any kind of future for my family and friends.

Blood had appeared on Dalen’s pillow, in his urine, his eyes. He had gotten used to the pain, the constant burning like thousands of tiny matches being lit within his veins. But now when he looked in the mirror, he saw it: the body of a watcher on his way out that he had seen on countless video logs. He watched cowards in black with masks on their faces loot stores and vandalize walls from last night’s video feeds; The World Awaits! Release us NOW! and The Only Way Out Is Up! painted onto the walls of city officials. He had seen the faces of these “Children of Earth,” knew that many of them worked in the stores they looted, came from important families. Of course, Dalen realized these generational uprisings were part of the city’s fabric just as much as he and his ancestors were, just as much as all of the wishes and secrets that allowed people to keep living. But like his father, Dalen wanted to leave some answers behind for his son, a few words of advice, truths he’d learned about their world. Dalen sat at his console, activated the camera, and began from the beginning:

“When you were younger I’d watch you in my monitors the first thing in the morning, how you lay in bed after waking up, just staring at the cave sky. At night, you’d kick the blankets off your feet before you fell asleep. And I’d say your name again and again, as if I were forming a chain of sound that could somehow make its way down to you. Enoch, I love you. Enoch, Enoch. Goodnight, Enoch. But, son, would you still even recognize my voice?”

Ora waited at the dinner table with her husband’s letter, waiting for Enoch to come home. She held her hands together to keep them from shaking, the wrinkled paper inside her right palm becoming damp. He’s a grown boy and has a right to keep his affairs to himself, she thought. But as long as he lived at home, he needed to share his life. The door opened and Enoch bolted for his bedroom without saying a word.

“Sit yourself down,” Ora said while blocking his path with her arm. “It’s like you’ve become someone else lately.” She placed the letter on the table and pressed out the creases. “What’s going on with you?”

Enoch sat down and avoided his mother’s eyes. He stared at the table, at the piece of paper under her cracked hands. “I know you’ve been worried,” he began. “But...it’s nothing you need to lose sleep over. I’m fine, really.”

Ora unfolded the letter and pushed it across the table. “Your father left this before he disappeared. It’s not much...but he wrote something for you that I’ve never been able to figure. Maybe you can.” She studied her son as he read his father’s words, looking for an expression of familiarity, an “ah-ha” moment in his eyes. But if the words meant anything to him, he hid it well.

“So? Just sounds like the advice of a man trying to make himself feel better for leaving his family,” Enoch said. He pushed the letter back to his mother, trying to hold his composure. “There’s nothing to figure.” He excused himself to his room, leaving Ora without any concrete answers. But she somehow felt more certain, perhaps because of her son’s immediate rejection of his father’s words, that there had to be a connection between them.

In his room, Enoch stared at the map beneath his mattress, trying to remember anything about his father from right before he left. But the only thing that came was the memory of spying on his parents arguing one night, hugging his pillow tightly as he crouched by his bedroom door. Their yelling made his whole body shake, made him want to dig a hole and crawl into it. He felt like running to a faraway place, where you could fall asleep to your own heartbeat. But when his father went missing, after all the futile searching, he remembered feeling terrible for having even considered leaving. Enoch stared up at the cavern ceiling, wondering if his father was, in fact, up there. Part of him still hated Dalen, but he wondered now if he had it all wrong. He lifted his arms and waved.

Work accidents, imaginary affairs, fake murders and suicides, letters with no answers. Dalen recounted to Enoch the many ways in which the men in their family left the city. “But the letter was the best I could do,” he explained. “Every time I tried to say more, there was this painful crawling in my head like insects trying to dig deeper, biting at the folds that controlled my hands, my sense of right and wrong. It’s like I was being told to stop. But I couldn’t just leave. Some of the others just disappeared in the night with nothing for their families to hold on to. To me that’s worse than death. Not like I could bring myself to plan some elaborate demise. I wish I could have left you and your mother something that could have helped you through this time. God knows I thought I was going crazy.” Dalen looked out the window and unfocused his eyes until the maze of streets and walls disappeared and the city became a disc of light. He reached for his last journal, the final pages filled with a periodic countdown: Six days, three hours, seventeen minutes.

Four days, three hours, seventeen minutes. Talia was already waiting for Enoch at the lightning gorge when he arrived for their first date. She had laid out a quilt right at the edge, so they could lie and peer down together at the colonies of worms, pulsing like stars. They ate dessert rations they saved up—blueberry muffins and zucchini bread—and drank a small bottle of wine Talia had stolen from her father’s reserve. By all accounts they were having an exemplary first date. She talked about her future, plans to become a full-fledged horticulturalist. Enoch just nodded, echoing similar plans he knew weren’t possible. When he leaned in to kiss her, holding her tight around her slender waist, he thought that such softness wasn’t possible, the feel of her lips, the way his fingers seemed to melt into her body. “I like you,” he said. Talia reached into the gorge and wiped her glowing fingers on Enoch’s nose.

“Worm shit,” she said. “I like you, too.” They lay down curled into each other like a heart.

“Do you know what you’re going to ask the Watcher for on Wishing Day?” Enoch asked.

“I go to those events for the party. It’s a good time,” she answered. “But I don’t believe in any of that nonsense.”

“You don’t believe in the Watcher?”

“Oh, there’s a Watcher, but he’s probably just some guy. He might even be part of the problem.”

“What problem is that?”

“Um, us being down here. I’ll bet you anything that the world is perfectly fine up there. It’s a political thing, keeping us here.”

“You’re not making any sense. You’re starting to sound like those Children of Eden.”

“Would that be so bad? Just think about it. No one knows, or at least they pretend not to know, how long we’ve actually been here. All the stories give us a different number. And the last time people tried to storm the tower, they were all killed. Why not just let people in, so they can see for themselves? Why all the secrecy?”

“Sure the founders had their reasons. Maybe knowing would be worse. At least people can have their hope.”

“You can have your hope, Enoch. I’d rather know the truth.” Talia got up and gave Enoch a look of pity. You poor, clueless boy, her eyes seemed to say. “Look, I should go.”

“I didn’t mean to upset you.” Enoch handed Talia back her quilt, hoping that she’d push it back and decide to stay. He didn’t want things to end like this. His first and last date with the girl who could have been the one.

“It’s fine, Enoch. I’ll see you at Wishing Day.”

Ora came home to her son cooking dinner—again. He had changed in the past few days, talking more at home, wanting to go to the shops with her. Enoch had always kept to himself, and while not exactly selfish, he always needed to be reminded to say thank you or to help out around the house. She sat at the dinner table, watching her son talk about his day as he chopped vegetables, humming the Anthem of the Founders. Something was coming, and he was preparing her for it. And while she had no idea what that something could be, no evidence to connect her son to Dalen, a part of her already knew that her house would feel emptier soon. She got up from the table and embraced her son.

“I love you,” she said. “I know things changed after your father left, but I never stopped loving you any less.”

I wish you could watch me find someone that I want to share my life with. I wish I could give you a grandchild. I wish you could see me grow into a man that you’re proud of. I wish I didn’t have to leave you alone (Uncle Terr and the cousins from hell don’t count). I wish I could offer you more than this note, but know that I’m okay and that I love you. I wish you could see me after tomorrow, but I’ll see you.

Dalen watched his son slip out of the house in the middle of the night. The streets were empty, save for the occasional team of custodians cleaning and preparing for Wishing Day. Enoch allowed his instincts to guide him, closing his eyes to see the map more clearly as he worked his way into the inner rings. But from an alleyway not far from home, a figure in black emerged, following Enoch from a distance. As Enoch traveled deeper into the city, more joined this figure from other districts, anxious specters descending without his knowledge. How Dalen wished he could have sent a message to his son somehow—open the window and cry out, “Behind you!” But there was no way of warning him. And the tower’s plasma cannon had been dismantled by his father, leaving only an antique long-range rifle at Dalen’s disposal, a .338 quantum warfare super magnum. Dalen had never fired a weapon before, let alone at a target over a mile away. He examined the gun awkwardly and began loading.

At the “Ascension of the Children” mural, Enoch could now see highlighted in his vision the seams of a small, hidden passage, just wide enough for a person to crawl through. He pried at the square area with a utility knife until the panel came loose. The shaft was only about twenty meters long but was armed with two laser grids, volleying back and forth. Enoch threw in a crumpled piece of trash, which was immediately sliced to confetti. On the lower lip of the opening was a small console with a series of buttons, flashing colors at melodic intervals. Enoch closed his eyes and tried to let the tower guide him. He remembered the flashes of color in his visions, but he wondered about the timing of it all. After studying his journal, he realized the colors represented musical notes, and that the numbers the tower had helped him calculate translated into a melody—specifically, the anthem of the founders, that old folk song he couldn’t seem to get out of his head. Enoch hummed the tune as he followed the lights. Red, blue, yellow, yellow green. Red, blue, yellow, yellow green. He punched in the sequence and the grids shut off.

Sweat dripped from Dalen’s brow as he followed the specters through the rifle’s scope. The one who had been leading the pack inched further as Enoch pushed himself through the ring wall. Dalen’s hands trembled. He centered the crosshairs on the figure’s torso, closing his eyes as he pulled the trigger. The sound, like lightning cracking against the cavern, startled him, and for a moment he thought he had entirely missed the shot. But as he positioned the rifle again and peered through the scope, he saw that the specters had scattered and that the black figure behind his son crouched in pain.

Enoch had just exited the shaft when he heard the gun’s report followed by the groaning of someone on the other side. He turned around and saw a woman in a mask and a black jumpsuit, writhing her way through while cradling her left shoulder soaked with blood.

“Whoever you are, you need to go back now,” Enoch yelled.

The figure stopped and looked up before removing her mask—Talia.

“I’m hurt, Enoch,” she said. “Pull me through.” Her legs still hung outside the entrance.

“You need to go back. What are you doing here?”

“We need to know the truth,” she said, almost in tears. “I need to know.”

Enoch could hear a whirring sound getting louder in the shaft. The security measures were powering up again.

“You need to turn back now. The shaft is protected,” Enoch said. He pleaded with her, his voice cracking as he realized that it was already too late, that Talia was never going to turn back. “Please, listen.” There was no console on the other side. The lasers appeared in the middle of the shaft, each net working their way out. Enoch looked into Talia’s eyes as she stared silently at the green lattice inching toward her. He turned away and heard a brief scream, the apparent sound of burned flesh sliding against burned flesh. Enoch turned around and stood still for a moment, hardly able to comprehend what he saw. Cubes of her—an eye, part of her lips, sections of her nose. Her legs still hung out the other side, spasming like the tail of a severed snake. Enoch didn’t want to leave her like this, but the tower still beckoned, guiding his body through the tomb the inner rings had become.

He breathed in the old city and what these people once were. Skeletons in black jumpsuits had been piled by doorways, bags of bone and dust with name tags, jewelry, and suitcases—the bodies of mothers, fetal and arched over their children—rib cage to rib cage. These black gloved skeletons held knives and sharpened stones and the last guns few would ever see. They had rallied as Talia rallied, fighting for a glimpse of the surface. Enoch began to sob as he walked on, making sure to take note of the numbers on the wall sconces he passed, calculating the circumference and diameter of the city, calculations he knew he would need to leave this ring and enter the tower chamber.

“If I had been a better shot you wouldn’t have had to go through with that,” Dalen said into the camera. “She would have dropped to the ground masked and nameless and you would have been none the wiser. Now, you’re going to carry that moment with you up here just like I’ve had the blood of another man on my hands. He followed me like she followed you, but made it through to the other side. We had no guns, no knives, nothing with which to harm each other except for the bones of the long-deceased scattered on the floor. We exchanged blows, and I held my own for a time. But he was a large man, and when we took the fight to the floor, he pinned my neck down with his knee. I reached for anything I could grab hold of before I passed out, my fingers eventually finding purchase inside the skull of a child. It was defense. It was for the city and tower. But there was something more, too (and not just the gentle tweaks the tower was making in my mind). And I’ve thought a lot about what that something else might be—and all I can come up with is wanting to feel one last real thing with another person before I spent the rest of my life alone.” Dalen logged off and wrote in his journal: Two days, three hours, seventeen minutes. He rolled into his cot, wincing as the tentacled pustules on his body touched the mattress and covered himself with a blood-splotched sheet, trying to give into exhaustion if only for moment.

A part of Ora knew that Enoch had left the night before, but she still called out to him to tell him breakfast was ready before opening his bedroom door. An empty bed, a letter on the nightstand, and a half cleared out dresser. She traced the indentations of her son’s body on the mattress and lay down, reading his last wishes. She buried her face into a pillow and cried, wiping her eyes dry with the top sheet until she felt something sharp poking her eyes—a nail trimming? No, a splinter. She held the crescent sliver of wood up to the light. Beside the bed, she noticed more shavings. She got up and examined where they might have come from, eventually lifting the mattress and finding an elaborate map of the city.

Children marched through the streets dressed in costumes of the past—police officers, army soldiers, astronauts, animals like elephants and giraffes that had either long gone extinct or were unable to be saved due to their size. A restored army jeep trailed their steps, displaying the city charter in a glass case. The engineer core, descendants of the city’s builders, waved to people and passed out replicas of the same layout that was used in construction. Dalen ate his last meal, mashed potato and meatloaf packets, and watched the festivities through his scope, his wife sitting outside of their home, trying to be strong. The Founders Wish ceremony was about to begin. Crowds gathered around a stage in the fourth ring’s agora with a banner overhead reading: We Wish As One.

The mayor spoke over the PA. Dalen couldn’t hear his words, but he could practically recite what was said. It was the same speech every year: about the city as a cocoon, how the founders wished for the cities to emerge stronger as a people, as a new nation. Dalen often wondered how much the ruling families knew about the tower, his family, everything. Someone, after all, had been restocking the tower with supplies over the centuries. The mayor, a jolly, bearded fat man (weren’t they all?), smiled gregariously after his opening remarks. He extended his arms in a dramatic gesture that made many of the younger people roll their eyes, and invited the city to join in a moment of silence and wish as one before any stone was cast. The city grew quiet.

As Enoch passed the final gate’s security, he found himself in a dark corridor, hidden from the lights of the cavern. He felt his way through the steel passage, walking for hours, imagining himself in a coil surrounding the heart of the city. Finally, he saw light ahead and found himself in a moat of wishing stones around a moss-covered mound. At the center, stood the tower. The sides of the mound were steep and Enoch struggled to gain purchase on the slick surface, precariously clinging to loose rocks and patches of soil. He slid back to the moat twice before making it, badly scraping himself. Nearly breathless, he sunk his fingers into the ground and pulled himself to the top, suddenly confronted with the sight of alternating spirals of limestone and titanium that seemed to go on forever.

On the limestone, history and culture had been carved in several languages, the levels at the base describing the first major cities of early civilization—Memphis of Egypt, Uruk of Sumeria. Poetry, songs, religious text, chronicles of war, and the names of kings could be found as Enoch walked around the tower. The metal spirals held the evolution of scientific knowledge—the astronomy and math of the Greeks and Babylonians, medieval forays into the functioning of the human body and soul. Somewhere up this tower, thought Enoch, were real answers about what had happened to the world. The tower doors, grand as the structure itself, stood nearly fifty meters high; if the stories were to be trusted, they were made from the melted riches of the ancestors. Beside the doors, cut into the tower itself, was a small rectangular crevice next to a carving of a hand. Enoch looked up at the height of the tower again and slowly inserted his palm into the opening, feeling indentations where he could rest his fingers. He felt a sharp pinch and immediately pulled out—a puncture wound on his middle finger, a small droplet of blood. Enoch could hear the colossal gears of the tower begin to shift, moving the monolithic deadbolts. The doors slowly opened, welcoming the next Watcher.

On his feeds, Dalen could see the first of the wishing stones being thrown—fathers helping their children, teenagers throwing stones just to throw stones. He could see Ora in the crowds, still in her nightgown, a stone in hand, weaving through people as if she were sleepwalking. She looked up at the tower for a long moment and threw, her wish landing halfway up the tower’s mound before rolling down into the moat. Dalen wished he had the time to go down there and read what she wrote. But he knew the wish wasn’t for him; it was for his son. And in his last hours in the tower, Dalen wanted to finish giving Enoch answers to questions he might have: Why stand guard in the tower at all if no one seems to have the answers? “It’s not like we have any say in the matter.” Will the world ever heal? “If it does, I think we’ll be long gone.” What about the other cities? “We haven’t heard from anybody in almost two-hundred years.” Did you love me? “More than you’ll ever know.” Where did you go? “I have thought of three scenarios, dreamed of them in detail really ever since the tower called you…

In one, I leave the airlock and never look back. I’d have two hours or so with a suit on if I conserve my breath. I’d travel north as my father did and comb the land for signs of his body. In my dreams, I’d always find him. He’d be laying with his arms and legs spread out like he was waiting for the world to consume him. I’d take his suit off and use his helmet as a headstone. And then I’d start digging a hole large enough for the both of us. First I’d put him in and then I’d join him at his side. With the storms being what they are, the hole would be full of sand and soil soon enough. Perhaps you’d join us later, maybe even the others who come after you. And so, at least in death, we’d all be together—those that watched the world below becoming part of the world above.

But then there’s the selfish desire to see you. And in this scenario, I’d leave the tower without my suit just as you entered the control room. I wouldn’t last long outside, but if I held my breath, if I brought a hand-held respirator, I could last long enough to knock on the glass of the dome and wave, holding up a message that said something like: I love you, son. Stay strong here. You would wave back and the urge for you to go to the airlock to save your father would be great, or so I’d like to think, but I would stop you. And after we had seen each other, I would walk away for what little time I had left. I would walk towards the beach, imagining the pictures in the books I studied as a child, knowing I would suffocate and collapse or die from the tower’s illness long before I ever got there.

And then there’s this small cave I’ve seen from the dome. Or what I think to be a cave—maybe you won’t see anything. I’d walk there in a suit, and once there would take my helmet off. I’d travel deeper into it for as long as I could breathe, and I’d discover that life flourished here—insects, amphibians, small mammals. A tiny paradise as a sign of what is to come one day. I’d find a flat rock to rest on and would welcome death in the house of new life.”

The interior of the tower seemed impossibly massive in comparison to the outside, lit not by cauldrons of worms but by the yellow light of the surface. Ramps and stairwells ran along the walls, lined with crates of food and medicine. A stone water well with pipes leading all the way to the top was located near the center, and next to it, a small steel cage, a pedal-powered elevator just large enough for one person. Enoch examined the rickety contraption, but decided to take the long way after calculating the risk of the frayed cables and rusted pulley system. The interior had been carved with history, not with the battles and milestones found in books, but with the names and voices of the first citizens who descended from the surface for a second chance: Bryan, Rachel, What goes up must come down, Easto, Wilhoff, Remember the Alamo, Joey, Daniel, Bucciaglia, Andrew, We’ll be back soon, Chicago Deep Dish will survive. Some of these family names Enoch knew but many of the sentiments and first names belonged to an era that had long passed. He looked up at the light of the sky and continued the long hike ahead of him, running his fingers along the names of the ancestors.

“You’ll be here soon, son. I wish that you could have a different life. I wish you the best of luck while you’re up here. I wish that, by the grace of God, something miraculous happens for the city while you’re watching over it. I wish that I could stay just a bit longer, so I could hold you and tell you how proud I am. I love you.” Dalen saved his logs and downloaded them to a memory drive, placing it on his son’s bed. He climbed up to the dome, the starry blisters on his hands exploding with each rung, and entered the antechamber to the airlock, filled with eco-suits. He peeled off his clothes and stood next to the the glass, two feet thick, separating his withered naked body from the poisoned world, and imagined the city skyline as it once was long ago. The sky was bright orange, and the sun had emerged from the clouds. In the distance, Dalen could see the cave, which may very well have been the rubble of a collapsed building, a valley of sand dunes that marked the direction his father traveled, and what used to be the shoreline of Lake Michigan beyond the ruins of Navy Pier. Like his son, one more wall stood between him and whatever would come next.

About the Creator

Sequoia Nagamatsu

Fiction has appeared in ZYZZYVA, Redivider, Hobart Web, and West Branch Wired, among others. He co-edits the literary journal Psychopomp Magazine.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.